Thoughtwax

Interface nostalgia

Monkey Island, a videogame originally developed twenty years ago, came out for the iPhone this week [App Store link]. In order to avoid the shocking anachronism of blocky VGA pixels on the crisp iPhone screen, the developers wisely decided to update the game’s sound and graphics to make the old thing a bit more palatable to players who may be younger than the game itself. It’s a sign of a good game that a bit of spit-polish can bring it right up to date, but you might also think it’s a bit of a shame that the original classic has been papered over. Where’s the reverence? Nostalgic gamers must make up a decent chunk of the potential market for a smudgey Monkey Island, and they’ll miss out on reliving the original glory.

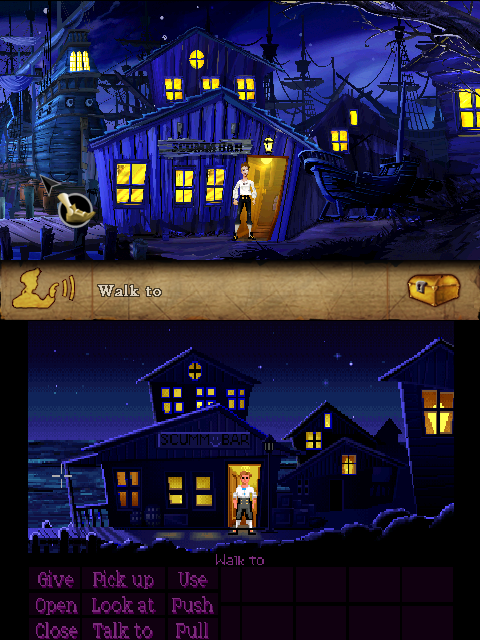

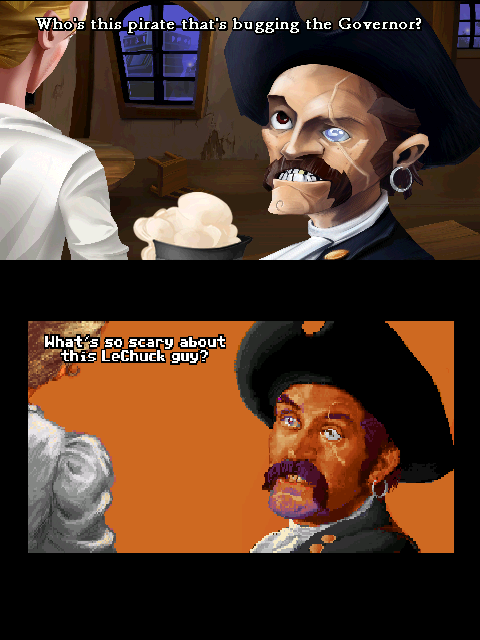

The developers did something else clever too, though, and this is the really interesting bit: players can toggle between the old and new version. At any stage, swiping across the touchscreen with two fingers rewinds the user interface by two decades to reveal the original artwork, fully playable. And I can tell you, it’s the most compulsive UI interaction I’ve encountered in ages.

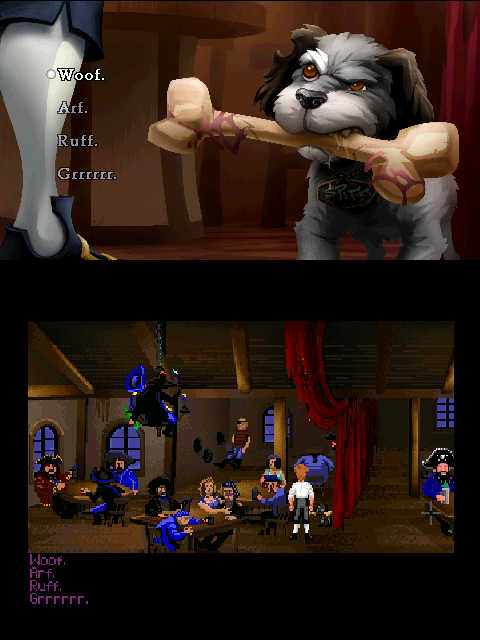

There are two levels of memory triggered by playing the game with this feature. Entering a new location in the game, complete with up-to-date graphics, activates a narrative recollection of the original: oh, I remember the drunk pirates in the Scumm Bar, I remember insult swordfighting. In fact, nothing about the new design seems out of step with my recollection of the original game at all. I literally don’t register a difference. The situation and architecture, the general outline of the scene, are more than enough to bring it all back. The combined framework of game screens, the defined routes through them and puzzle objects reminds me of Kevin Lynch’s idea of imageability, where mental maps of cities consist of edges, paths, and nodes. Turn a corner in the game and the latent memories awaken, just like stumbling back into an almost forgotten part of a revisited city.

Only you’re not playing the game as your previously experienced it at all. The second facet of recollection comes with the UI switching. Flicking over to the old graphics – and I, for one, found it almost impossible not to do so on every screen – shows you the game as you originally experienced it, and it looks completely different. Suddenly you remember the old imagery too. Conceptual memory gives way to visual memory, in a clear illustration of how the mind functions on different levels. It’s an odd experience, first thinking you recognise something, then discovering that the original was in fact quite different, but that you now remember that too, as additional detail. In one way it’s a contradiction, and in another it’s sharper focus. You’re faced with how brittle your recollection must actually be, and how susceptible to persuasion and malleable memory is. It’s become a meta-game for me, trying to recall what’s different before flicking over for the reveal.

As I play through the game I’ll collect interesting before and after shots in this Flickr set.

Bonus link: Fans shouldn’t miss lead designer Ron Gilbert’s notes on playing Monkey Island through twenty years later.