Thoughtwax

Automating Yourself Out of a Factory Job

Anthropic co-founder Jack Clark on Tyler Cowen’s podcast:

COWEN: Silicon Valley up until now has been age of the nerds. Do you feel that time is over, and it’s now era of the humanities majors or the charismatic people or what?

CLARK: I think it’s actually going to be the era of the manager nerds now […] We’re going to see this rise of the nerd-turned-manager who has their people, but their people are actually instances of AI agents doing large amounts of work for them.

COWEN: It’s still like the Bill Gates model or the Patrick Collison model.

CLARK: The “people who have played lots of Factorio” model, yes.

I haven’t played lots of Factorio, but I’ve played a little! Not sufficient to become the next Collison or Gates. But comfortably enough to opine about it on my blog.

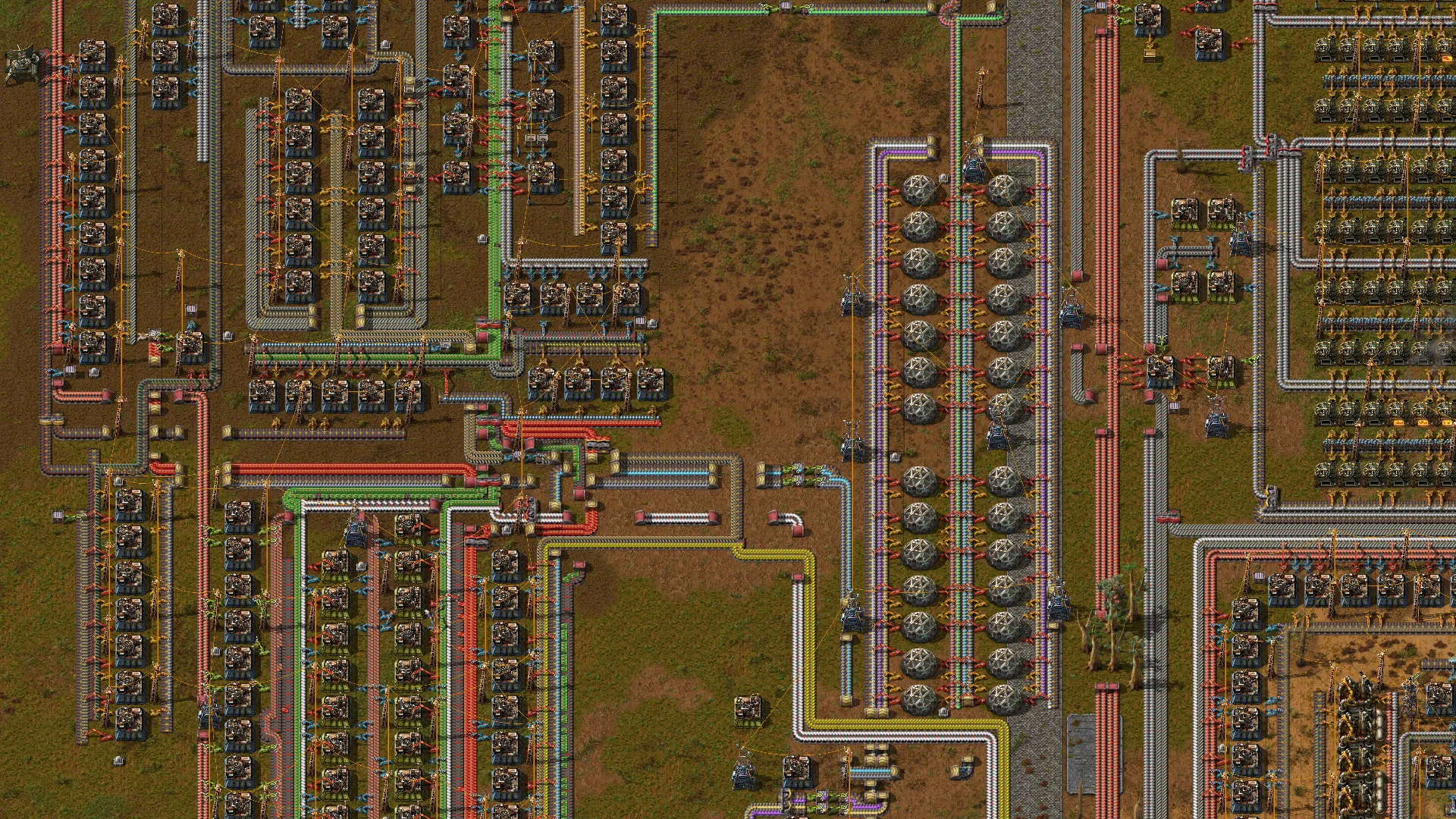

A brief explainer. Factorio is best described as an automation simulator meets survival strategy game. You’re a little guy who has crash landed on a planet, and you have to build machines that in turn build more complex machines, until you can eventually build a rocket and fly home. You’re basically trying to speedrun the bootstrapping of industrial production. Think The Martian, but instead of growing potatoes, you’re growing an entire technology tree until you get to interplanetary travel.

This requires a lot of resource-gathering. However unlike games like Minecraft, the only reasonable way to do that is to automate absolutely everything by constructing increasingly complex production lines.

It’s similar to “engine building” board games like Wingspan or 7 Wonders, where you start with a small set of resources that you must combine into an interlocking flywheel of ever-increasing value. Here the engine is literal (conveyor belts, refineries, lab) but the underlying dynamics are the same. Factorio is ultimately a game about system design.

You have likely by now decided whether Factorio meets your own personal criteria for “fun.” I get it. The pleasure of the endeavour is in the immense satisfaction to be had when your entire Rube Goldberg-like construction finally clicks into place, inputs and outputs whirring away in perfect equilibrium.

The frustration is that it’s really, really hard. A few hours in and I’m still on the tutorial, and possibly stuck there. Simple designs quickly sprawl into unknowable spaghetti. Parts break down unexpectedly. Every fix leads to a new error elsewhere. If you don’t plan carefully things can get brain-breakingly complex fast.

It is, in other words, an ideal metaphor (and perhaps training ground) for the wonder and frustration of wrangling AI. Especially for AI-assisted code generation.

Firstly, your simple plan can often feel like it’s teetering on the brink of some unexpected cascading failure. You’ll sometimes find yourself debating whether you’re better off salvaging your current efforts of just starting over from scratch.

But Factorio also pushes you towards a mindset that prioritises automation over manual work.

One of Google’s many aphorisms in mid-2000s was that you should try to “automate yourself out of a job.” This probably sounds trite now but was a genuinely subversive idea to me at the time, and part of what made the version of Google such a fun and mind-expanding place to work. “Automate yourself out of a job” was a reminder to focus on your outcome, not your output, and what’s more it was permission to approach everything through that lens.

The irony today is that many people are now discovering that they have not only permission but a mandate to figure out how to, well, automate themselves out of a job. In a stunning turn of events, software development is one of the first areas of the economy being dramatically changed by AI, and we all have to figure out how to adapt.

Much of the energy and discussion has naturally centred around the tools. What coding capabilities wiil the next models have, how will the designer workflow change, which hot new product do I have to learn? It’s hard to just keep up.

But the real shift isn’t in the tools, it’s in how you think. :mindblown:

It’s not unlike the shift that happens when a designer “switches track” to become a design manager. Whereas before their job was to design stuff directly, now their job is to somehow wrangle and steer the work of other designers towards a decent outcome. You can be a force multiplier for sure, and that’s part of the appeal. But at first it can be tricky to figure out how to work the controls, so to speak. It’s a skill you need to develop.

I used to think “prompt engineering” was a temporary hack–a crutch while we waited for better UIs for controlling LLMs. I’ve since changed my mind. Now I can see that it’s an enduring part of how we’re going to use computers. And in that sense, it’s not unlike running a great design crit. Just like your team, you’re going to have to get to know these AI Agents and how to tailor your approach to cajole the best results from these new team members.

Interestingly, many best practices in prompting should already look very familiar to anyone who has spent time giving design feedback in a crit: in both cases you’re critically analysing what you’re seeing, providing context, making appropriately specific constructive suggestions, etc.

Leaders sometimes say their job is to manage “the machine that builds the machine.” We are now entering a kaleidoscopic era of machines that build machines, agents that control agents, inputs and outputs, systems and feedback loops. Lucky you to have all that relevant experience!

This is the planet we have crash-landed on. The manager nerds have begun building factories.