Thoughtwax

Oats

One way to think about the industrial revolutions is every time you figure out the industrial revolution, you’re finding some way of bypassing a constraint or bypassing a bottleneck. The bottleneck prior to what we call the Industrial Revolution was metabolism. How much oats can a human or a horse physically digest and then convert into useful mechanical output for their peasant overlord or whatever?

Nowadays we would giggle to think that the amount of food we produce is meaningful in the context of the economic power of a particular country. Because 99% of the energy that we consume routes around our guts, through the gas tanks of our cars and through our aircraft and in our grids.

Right now, the AI revolution is about routing around cognitive constraints, that in some ways writing, the printing press, computers, the Internet have already allowed us to do to some extent.

This is an excellent analogy, but perhaps only partially complete. We’ve been externalising bottlenecks since forever.

When humans got smart enough to start cooking food they were externalising digestion, which led to smaller guts and jaws, which in turn freed up energy for even larger brains to develop. Modern humans are the only animals that require their food to be cooked, but are also the smartest; an evolutionary tradeoff that turned out to be a winner.

So now we can try to fill in the blanks:

- Cooking (2M years ago): Externalise digestion → energy surplus → bigger brains

- Industrial Revolution (250 years ago): Externalise metabolism → energy surplus → bigger economy

- AI Revolution (2 years ago): Externalise cognition → cognitive surplus → ???

If externalising digestion gave us intelligence, and externalising metabolism gave us industrial civilization, what does externalising intelligence give us? And if each of these steps bootstraps the next, and are apparently happening exponentially faster, then…?

Just as it would have been impossible to predict the impact of cooking or the steam engine (the OG GPT!), we have no way of imaginging what will happen as a result of AI. The main difference is that this time we seem capable of seeing the thing coming, but still have no way of remotely knowing what it is.

Recent reckons

For the third time in as many years, I sat down with Intercom’s Chief AI Officer Fergal Reid to discuss the current AI landscape. Here’s the full episode:

It’s fun to have had these “state of AI” type chats at different points in the history of this all unfolding. Give me a half-wrong contemporaneous take any day; hindsight is for the low rollers. Previous episodes in what you could now call a series: June 2023, August 2023.

I was also on Ridd’s mighty Dive Club podcast recently, talking about how the role of design in tech companies is evolving:

2027: Race to AGI!

I made a game! 2027: RACE TO AGI! is a satirical game about the wild world of Artificial General Intelligence research: where good intentions meet impossible choices, and the future of humanity is at stake!

You are the fresh-faced CEO of OpenBrain, a leading AI lab. Can you navigate a series of near-impossible decisions to achieve ALIGNED SUPERINTELLIGENCE, or will it be GAME OVER for humanity?

👉 Play it now! 👈

I designed and coded this over a total of about 20 hours using mostly Claude Code and Midjourney. The bulk of the time was spent on playtesting the game itself and fixing small UI issues.

That might sound pretty chill, but the last mile problem for production-ready UI is still very real. User expectation for game UI performance is high, and getting rid of web jank was a pain. Just like in the real world, 90% of the work happens in the last 10% of the project.

Like many people I have a digital junk drawer full of half-finished vibe-coded experiments. Here I mostly wanted to learn by forcing myself to actually complete something bigger than a one-day project. Vibe coding sometimes reminds me of the the observation about modern art: “I could have done that” + “Yeah, but you didn’t.” (The source code is on Github).

Finally, I wanted to explore the topic of the game, AGI research.

During testing I only managed to reach the successful end state of “Aligned AGI” a couple of times. (There are several unique game over states.) I realised that my game was clearly too hard, and made a note in my TODO.md file to revisit the difficulty curve.

But as I continued testing, I noticed myself making in-game choices that were only to the end of winning, as opposed to making the correct choices. That is, I wasn’t making decisions as much as I was simply trying to beat the game. I wondered how powerful that pull must be for a real person in real life.

And so I mostly left it as it was. More than attempting to model reality, the best cautionary lesson here may be that in games like the one we’re currently playing, there are many ways to lose, and very few to win.

That said, if you do manage to beat the game, take a screenshot and send it to me! I’d love to know that at least one of us can do it.

Live-coding music with AI

Here’s a little piece of music that I co-created with AI.

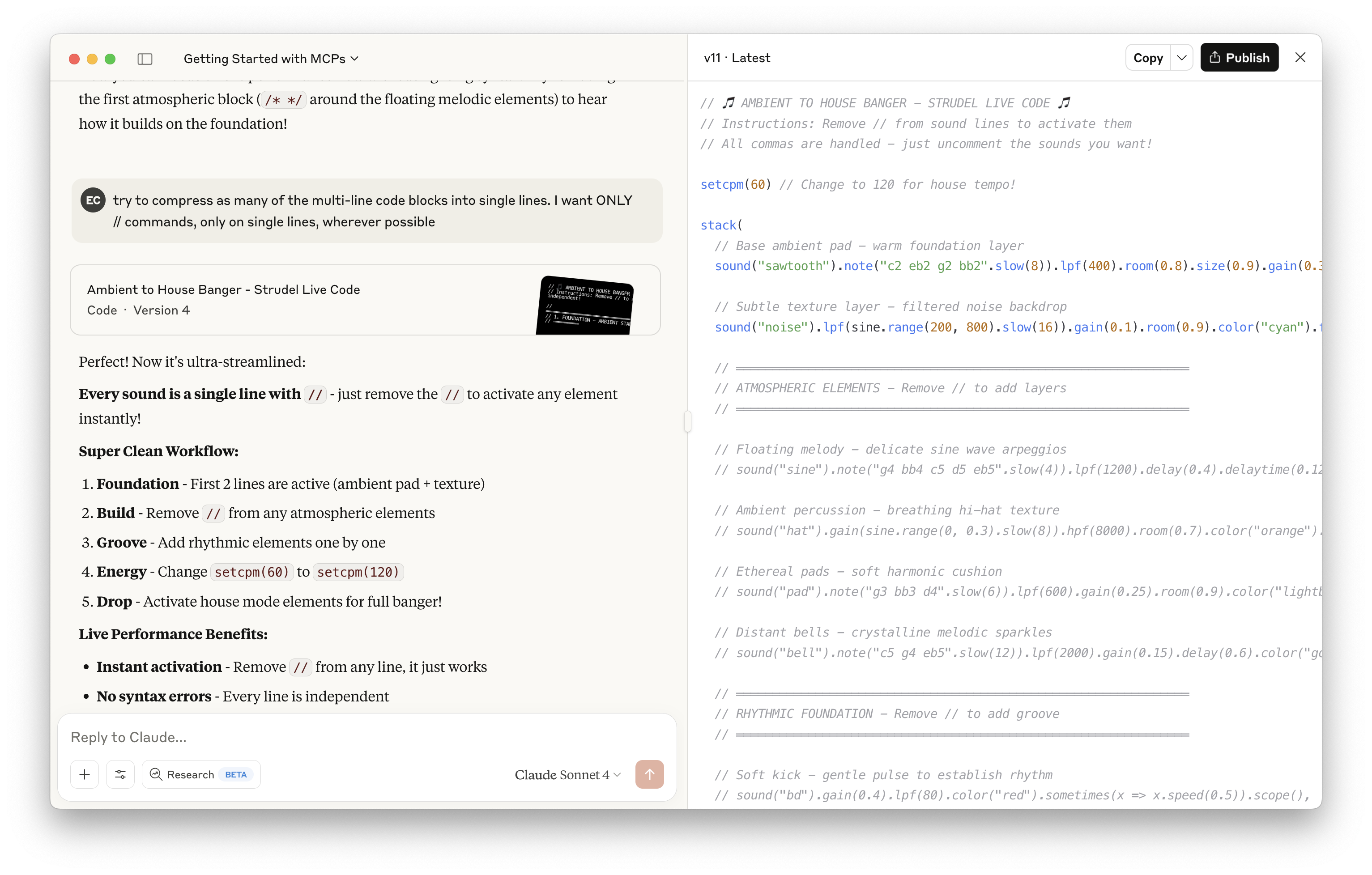

First, I prompted Claude with a description of the style I had in mind, and asked it to write some Strudel code. Strudel is a simple web-based REPL for live coding; live coding is where you play music by editing code in real time, and as you type the music being played updates accordingly.

I’d never used Strudel before, but soon figured out that the code from Claude wasn’t perfect, e.g. it had hallucinated some sample filenames that don’t actually exist. But overall it was a great start, especially considering there is probably very little Strudel-related training data in the world to draw upon. So while each line of code needed to be tweaked manually in some way to dial it in, and a bunch of them were rejects, it was like choosing from a curated bank of samples that I could then whittle down.

Once I started to figure things out, I realised I was mostly commenting in or out chunks of code to build or reduce the mix. So I pasted my latest version back into Claude and asked it to restructure the code for easier live performance.

I ran the Strudel output through an audio interface, into the lovely Chroma Console effects pedal to add some texture and swoosh (also operated in real time; need more hands!), then back into my computer to record.

I should also give an appreciation for Strudel’s cool little visualisations that you can turn on or off for each sound. It’s fun and novel to see the output interleaved with the code that creates it, and they reminded me of Bret Victor’s explorable explanations.

The video above was my second attempt at actually recording anything. Would I claim this music to be of distinct artistic merit? No. Would I listen to this at home? Also no. But that’s got more to do with the dilettantism of the human involved (~4h total effort, including this post) than the fault in the machines. I play music regularly and I’m intigued to keep noodling here.

The clacking of the mechanical keyboard was a mistake, but then seemed appropriate, so I left it in. The Strudel code used in the video above is on GitHub.

This is where I’ve found AI to be most useful creatively: you can parachute directly into the middle of someplace you’ve no real business being, and then just start breaking things to see what happens.

Cursor's MAMP moment

I bear no ill will towards my fellow nerds who treat their little computer setup as some sort of shrine, a little bonsai project in your laptop to be lovingly tended. Tend on, friend. I am with you in spirit.

But! I am a designer, and thus I take joy in finding faults in all things. And since I’ve been spending much of my free time prodding at the New Thing just to see what it does, I can no longer avoid the fact: while AI-assisted coding products are indeed marvels, using them still kinda sucks.

I’m not talking about the true vibe coding products like Lovable, Bolt, V0, Figma Make. These are great from what they are trying to do. But in real use I have so far found them to be much more about the ✨vibes✨. The code in these products is secondary, presented like more of a progress indicator than anything you’re seriously expected to interact with.

Vibe coding: the return of the notorious Hovering Art Director.

Vibe coding: the return of the notorious Hovering Art Director.

The “last 20%” problem for these tools will therefore likely persist for a little while at least, and I have not yet managed myself to use them to create anything that feels finished to me. Bad vibes.

Complexity as a feature

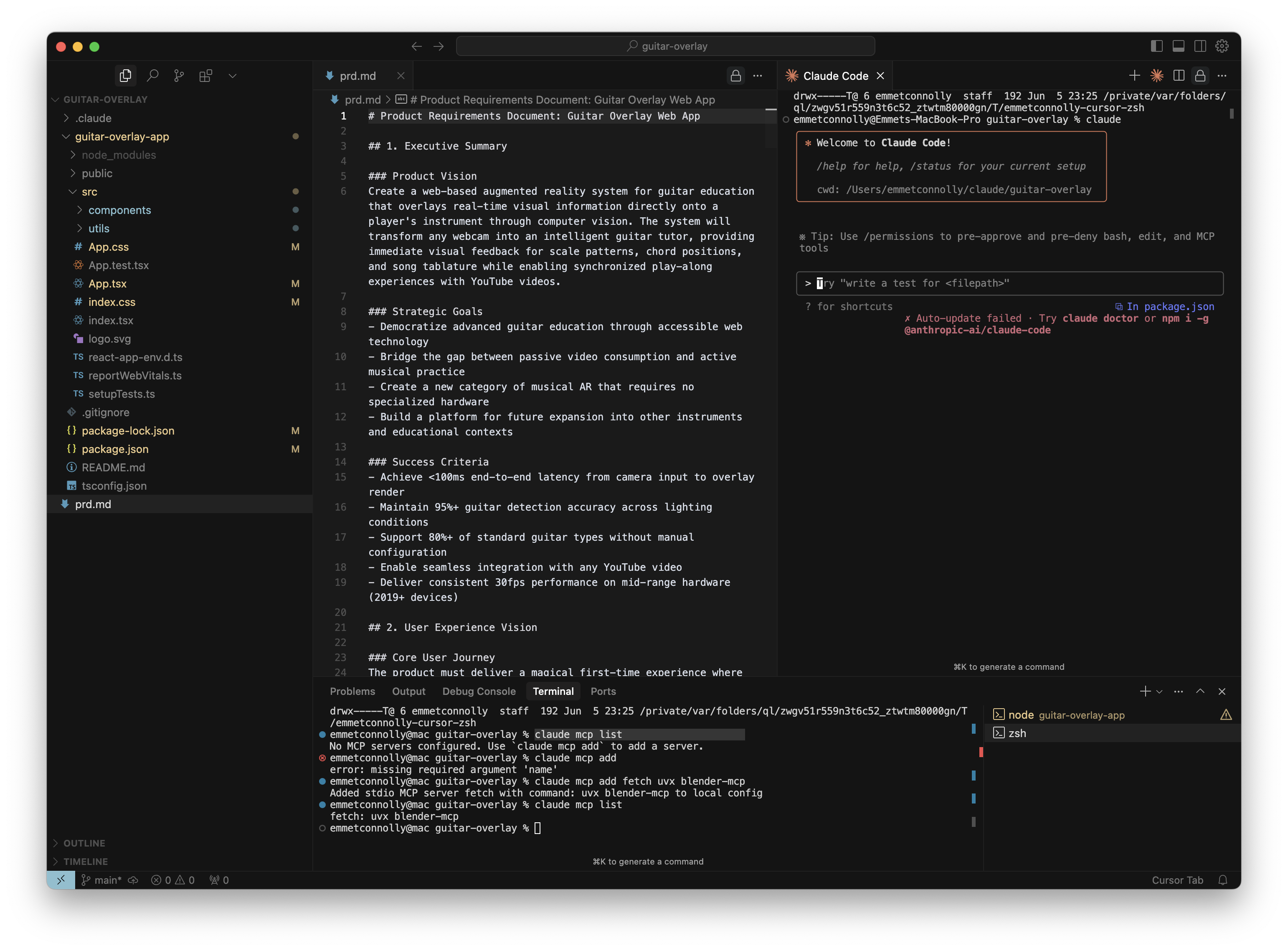

I am rather talking instead about using Claude Code to work on code locally on my own computer. Claude Code’s Opus 4 is a beast. It can handle everything from “Read this detailed PRD and start building” to “Fix this bug.” It goes beyond code generation: it has an almost unnerving levels of root access to your computer, it runs scripts, pushes to GitHub, controls tools via MCP, etc. It’s a natural language interface to the command line. Plus it has a charming and clever ASCII interface that makes me smile.

I am, as stated up top, a nerd. But I’ve never had this level of ability. I have some preexisting knowledge of code, and I generally enjoy doing things on the computer. I’ve done a bunch of tweaking to get my setup just the way I want it. In that spirit, here is my current setup, with Claude Code running inside of Cursor:

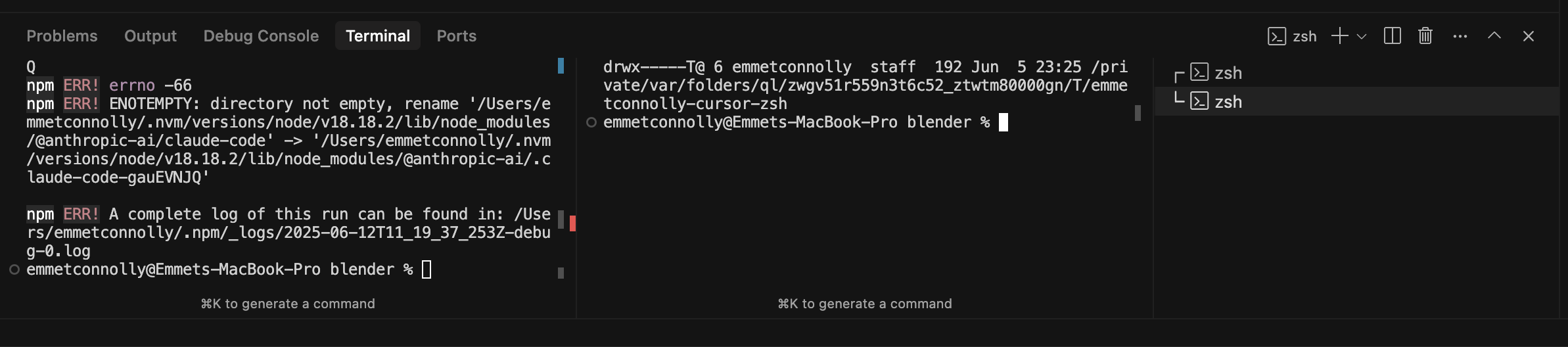

(To set this up: run

(To set this up: run claude from the terminal inside of Cursor, which will install Cursor’s native Claude Code plugin. Alternatively you can just run Claude Code directly from Cursor’s terminal.)

Isn’t this fun? I mean sure, it’s kind of a lot! But feels powerful and complete: like a single-window power-user cockpit for doing pretty much anything. Everything is in one place (that’ll be the I in IDE): my project on the left, the open subject in the middle (often just the PRD), my AI Agent on the right, and a terminal for running servers at the bottom. This is kinda what I imagine a future agentic operating system might feel like: a command centre for managing and observing multiple parallel tasks.

But/and. Isn’t this also kind of… bad? Look at it! Complex, intimidating, inscrutable. A normal person would never figure it out. It looks like an airplane cockpit for god’s sake!

(War story: I once travelled all the way to Mountain View to nervously present my early design proposal for Google Flight Search in a design review with Marissa Mayer, who was running Search back then. Her very first comment was, “Well, I guess it’s appropriate that this looks like an airplane cockpit!” followed by several minutes of hysterical laughter.)

How is this apparent contradiction possible? Why is the design of Cursor both perfect and terrible?

It’s because the TAM for “people who might reasonably be considered programmers” has grown orders of magnitude overnight, and in the process that group has suddenly transformed a radically more diverse group. Lots of new and different-thinking people are here now. The discipline of software engineering is about to experience its own version of Eternal September.

This newly misshapen market is therefore massively over-served with complex incumbent power user tools like Cursor. If this is already your natural habitat: as you were, this product is already highly optimised for neckbeards like you (and me). You are like a pilot who already knows how to fly the plane, and for whom an airplane cockpit is therefore the optimal interface.

Here comes the new guard

But lots of people just want to fly drones without needing to train as a pilot.

This new market will soon see new, more accessible IDEs that abstract away a bunch of the plumbing and constant breakage – all of the npm package update this and node server start that – and make it simpler and better. We have already established that there is a time and place for hobbyist tinkering, but it is not fixing package management when you’re just trying to get on with the pressing business of the day (an app that adds googly eyes to pictures of dogs).

The whole stack is a lumpy contradiction: incredibly powerful, impossibly fragile.

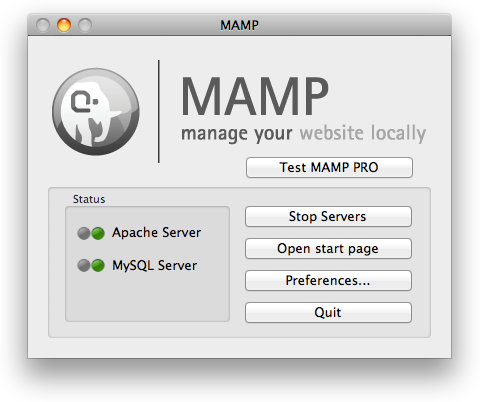

PHP and MySQL had a similar problem back in the day. Web designers could see that adding a bit of extra code to their HTML looked pretty easy. But setting up the LAMP stack was hard too. The coding part felt achievable, it was the infrastructure that was the hard part.

Then along came MAMP:

Ahh, that’s better. Look at the friendly little traffic lights there. And actual buttons for common tasks like starting and stopping your server.

Here’s what the equivalent task looks like today 25 years later, in Cursor (latest valuation: a cool $10b):

Running a couple of local servers should be easier than this.

Running a couple of local servers should be easier than this.

Cursor needs its MAMP moment. MAMP made web development accessible to people who didn’t want to wrestle with system config files or error messages. The power is there but the ease-of-adoption is exactly what most non-vibe AI coding environments are still missing. Coding remains very unevenly distributed for now.

Some of the things I’d like to see in a better IDE are practical: ability to manage multiple projects, an easy way to see and manage local development servers, automatic or simple source control wrapping, better native support for image and voice input.

But also, if you’ll allow me, the vibes could also be better. Think of a local, cozy, joyful, friendly studio space where ideas can manifest and break without consequence.

The models and vibes are here. What’s missing is the scaffolding that makes building feel like play again.

Automating Yourself Out of a Factory Job

Anthropic co-founder Jack Clark on Tyler Cowen’s podcast:

COWEN: Silicon Valley up until now has been age of the nerds. Do you feel that time is over, and it’s now era of the humanities majors or the charismatic people or what?

CLARK: I think it’s actually going to be the era of the manager nerds now […] We’re going to see this rise of the nerd-turned-manager who has their people, but their people are actually instances of AI agents doing large amounts of work for them.

COWEN: It’s still like the Bill Gates model or the Patrick Collison model.

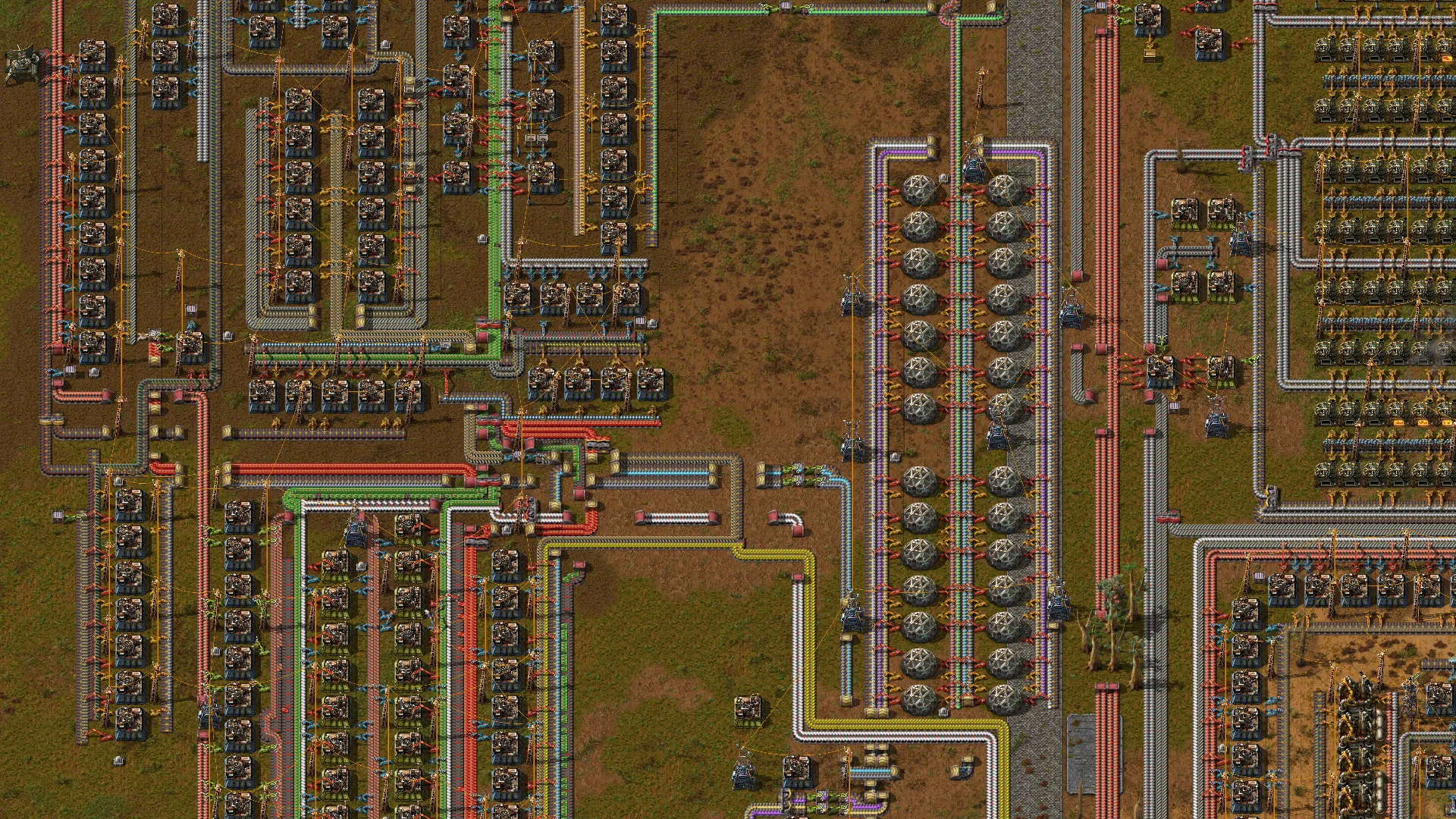

CLARK: The “people who have played lots of Factorio” model, yes.

I haven’t played lots of Factorio, but I’ve played a little! Not sufficient to become the next Collison or Gates. But comfortably enough to opine about it on my blog.

A brief explainer. Factorio is best described as an automation simulator meets survival strategy game. You’re a little guy who has crash landed on a planet, and you have to build machines that in turn build more complex machines, until you can eventually build a rocket and fly home. You’re basically trying to speedrun the bootstrapping of industrial production. Think The Martian, but instead of growing potatoes, you’re growing an entire technology tree until you get to interplanetary travel.

This requires a lot of resource-gathering. However unlike games like Minecraft, the only reasonable way to do that is to automate absolutely everything by constructing increasingly complex production lines.

It’s similar to “engine building” board games like Wingspan or 7 Wonders, where you start with a small set of resources that you must combine into an interlocking flywheel of ever-increasing value. Here the engine is literal (conveyor belts, refineries, lab) but the underlying dynamics are the same. Factorio is ultimately a game about system design.

You have likely by now decided whether Factorio meets your own personal criteria for “fun.” I get it. The pleasure of the endeavour is in the immense satisfaction to be had when your entire Rube Goldberg-like construction finally clicks into place, inputs and outputs whirring away in perfect equilibrium.

The frustration is that it’s really, really hard. A few hours in and I’m still on the tutorial, and possibly stuck there. Simple designs quickly sprawl into unknowable spaghetti. Parts break down unexpectedly. Every fix leads to a new error elsewhere. If you don’t plan carefully things can get brain-breakingly complex fast.

It is, in other words, an ideal metaphor (and perhaps training ground) for the wonder and frustration of wrangling AI. Especially for AI-assisted code generation.

Firstly, your simple plan can often feel like it’s teetering on the brink of some unexpected cascading failure. You’ll sometimes find yourself debating whether you’re better off salvaging your current efforts of just starting over from scratch.

But Factorio also pushes you towards a mindset that prioritises automation over manual work.

One of Google’s many aphorisms in mid-2000s was that you should try to “automate yourself out of a job.” This probably sounds trite now but was a genuinely subversive idea to me at the time, and part of what made the version of Google such a fun and mind-expanding place to work. “Automate yourself out of a job” was a reminder to focus on your outcome, not your output, and what’s more it was permission to approach everything through that lens.

The irony today is that many people are now discovering that they have not only permission but a mandate to figure out how to, well, automate themselves out of a job. In a stunning turn of events, software development is one of the first areas of the economy being dramatically changed by AI, and we all have to figure out how to adapt.

Much of the energy and discussion has naturally centred around the tools. What coding capabilities wiil the next models have, how will the designer workflow change, which hot new product do I have to learn? It’s hard to just keep up.

But the real shift isn’t in the tools, it’s in how you think. :mindblown:

It’s not unlike the shift that happens when a designer “switches track” to become a design manager. Whereas before their job was to design stuff directly, now their job is to somehow wrangle and steer the work of other designers towards a decent outcome. You can be a force multiplier for sure, and that’s part of the appeal. But at first it can be tricky to figure out how to work the controls, so to speak. It’s a skill you need to develop.

I used to think “prompt engineering” was a temporary hack–a crutch while we waited for better UIs for controlling LLMs. I’ve since changed my mind. Now I can see that it’s an enduring part of how we’re going to use computers. And in that sense, it’s not unlike running a great design crit. Just like your team, you’re going to have to get to know these AI Agents and how to tailor your approach to cajole the best results from these new team members.

Interestingly, many best practices in prompting should already look very familiar to anyone who has spent time giving design feedback in a crit: in both cases you’re critically analysing what you’re seeing, providing context, making appropriately specific constructive suggestions, etc.

Leaders sometimes say their job is to manage “the machine that builds the machine.” We are now entering a kaleidoscopic era of machines that build machines, agents that control agents, inputs and outputs, systems and feedback loops. Lucky you to have all that relevant experience!

This is the planet we have crash-landed on. The manager nerds have begun building factories.